Op-ed: Is MDE Cleaning Up Its Act When It Comes to Enforcement?

Russ Stevenson, Chesapeake Legal Alliance, and Katlyn Schmitt, Center for Progressive Reform

This op-ed was originally published in the Baltimore Sun.

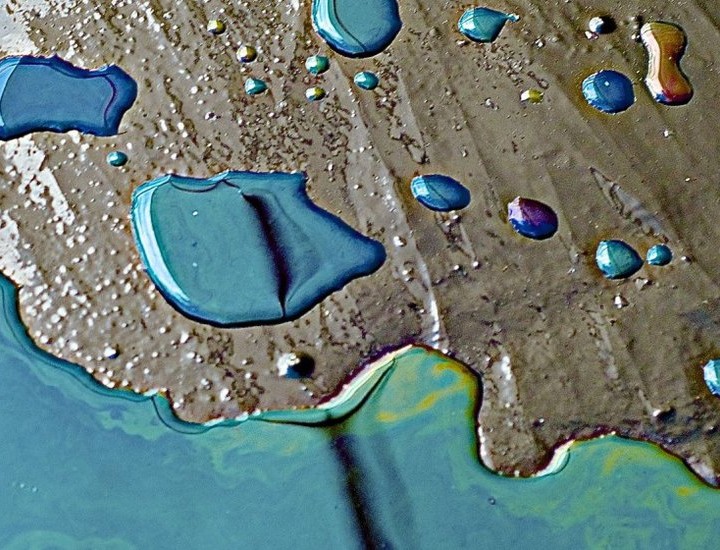

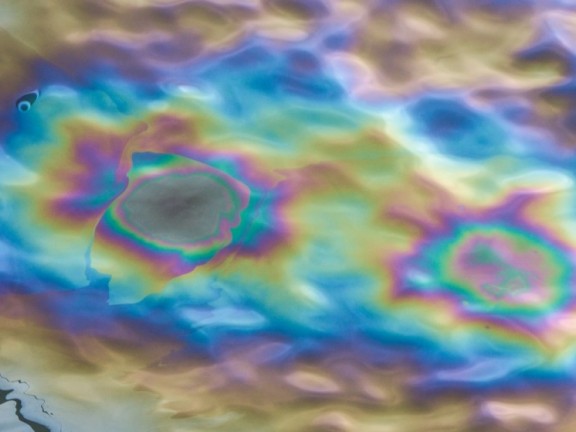

Dirty, polluted stormwater that runs off of industrial sites when it rains is a major cause of pollution to Maryland’s streams and rivers, and ultimately to the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland is home to thousands of such industrial sites, all of which are required by law to obtain a stormwater discharge permit from the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) to prevent pollution and protect public and environmental health.

Unfortunately, many of these sites do not have a permit. For example, our research in one small area of Anne Arundel County found that only four out of 12 industrial sites possessed a current permit. Of the industrial sites that hold a permit, many are not in compliance with the permit requirements. Between 2017 and 2020, MDE conducted just under 2,000 inspections of permitted sites throughout Maryland and found that more than two-thirds (68%) were violating the terms of their permits. These industrial sites are commonly clustered in urban areas, creating pollution hot spots of runoff that can include heavy metals and other toxins. Such polluted waters threaten the health of those who live nearby, who are more likely to be low income and populated by people of color.

The problem has been compounded during the Hogan administration thanks to MDE’s failure to impose consequences on violators in the form of fines or penalties. Based on our analysis, MDE’s own data show that by 2020, its efforts to enforce the Clean Water Act had declined by a whopping 77% percent from the average level from 1998 through 2015. In fact, MDE took enforcement action against only six of the more than 1,500 industrial stormwater violations its inspections uncovered between 2017 and 2020.

With no threat of serious sanctions, polluters have no incentive to spend money on cleaning up after themselves. They are free to wait until they are caught, knowing there will be no penalty for violating the law.