CAP Enforcement Scorecard: A Deeper Understanding

Importance of WSA’s Role in Clean Water Act Permitting Scheme

The Clean Water Act (CWA), as passed in 1972, was the first major law in the United States to effectively address water pollution, largely by creating an enforceable pollution permitting regime, with accountability and oversight provided by the federal government and citizens. The CWA serves to “restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation’s water” and does so by requiring EPA and the states to work toward the attainment of states’ water quality standards and by fully eliminating sources of water pollution.[1]

Any facility that intends to discharge pollution from its operation must apply for and be covered by a permit. These permits include technology-based and water quality-based limitations among other requirements. If permit holders fail to comply with the permit requirements or discharge a pollutant without permit authorization, they are subject to potentially substantial enforcement actions and penalties.

Some facilities require individual permits with requirements that are based on site-specific considerations, while other facilities must follow the blanket terms set under a ‘General Permit,’ where one permit applies to an entire sector.

Under the CWA, the EPA may delegate authority to implement the permitting program to states, tribes, and territories, allowing them to perform permitting, administrative, and enforcement duties. In Maryland, MDE’s Water & Science Administration primarily retains this authority.

Ensuring that Facilities that Require a Permit, Have a Permit

There are some facilities or sites that require clean water permits but do not have one. The stated goal of the Clean Water Act was to eliminate discharges of pollutants into navigable waters by 1985. We’ve failed to reach this goal by a long shot due to a myriad of reasons, including, but not limited to, lagging environmental enforcement and pollution from unpermitted facilities.

In Maryland, according to CAP and partners’ assessments, there are still many facilities that are operating without appropriate permits or operating with outdated permits. For example, a Magothy River Association (MRA) query of MDE databases found that, of the 12 facilities in the watershed that appeared to be subject to the industrial stormwater general permit, six facilities were operating without coverage, five had expired permits, and one site had coverage, but had only recently obtained it. Based on the low rate at which these facilities were properly permitted, there are likely hundreds of other facilities operating across the state without the required permit coverage and discharging untreated pollution in our communities and to our local waterways without any consequence.

Zombie Permits: Clean Water Permits “Living” Past Their Expiration Date

A review of data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Enforcement and Compliance History Online database in July 2021 demonstrated that many permitted facilities in Maryland are operating under outdated permits. This review revealed a backlog of permits for MDE to consider and renew that were beyond their five-year permit term and were either administratively continued or expired. A permit is administratively continued when it stays in effect past its expiration date because MDE, through no fault of the permittee, is unable to issue a new permit in a timely fashion (in response to a permittee’s timely permit renewal application).[2] If the expiration date of a permit has passed and the permit has not been administratively continued (no timely submission of permit renewal application by permittee), then the permit is expired.

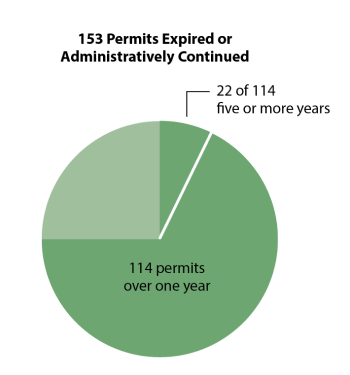

At the time of CAP’s data review, there were 153 permits that were either expired or administratively continued, and 114 that had been expired or administratively continued for over one year. Of those, 22 permits had been either expired or administratively continued for five or more years. For these egregiously delayed permits, an entire additional five-year permit term went by beyond the expiration date, without MDE analysis of the pollutants being discharged and the appropriateness of permit terms. After the period of significant delay, renewed permits may end up with more stringent terms than the prior permit. If MDE had not delayed in renewing these permits, some pollutant discharges to waterways from these facilities could have been prevented. These findings underscore the importance of MDE allocating adequate resources to permit renewals to avoid long periods of delay resulting in outdated permit terms. See August 9, 2021 Letter to MDE Re CAP Concerns Regarding Backlog of Administratively Continued and Expired Individual NPDES Permits for more information.

Understanding Maryland’s Clean Water Compliance Trends

MDE’s 2020 Enforcement and Compliance Report reflects the state’s downward trend in clean water enforcement over the last two decades. This includes record lows in enforcement related to surface water dischargers and stormwater management, with 22 and four enforcement actions for each program, respectively.

The low number of reported significant violations raises concern due to MDE's definition of "significant violation." MDE generally defines "significant violation" as "any violation that requires MDE to take some form of remedial or enforcement action to bring the facility into compliance."[3] MDE's definition of significant violations relies on the agency's own action to provide some form of remedial effort. This leads to reporting issues because if MDE brings fewer enforcement actions then the number of reported significant violations will decrease regardless of whether there has been a decrease in the number of actual violations.

A Case Study: Rampant Noncompliance with Maryland’s Industrial Stormwater General PermitMDE’s Water & Science Administration is responsible for regulating stormwater from approximately 1,200 industrial facilities – like processing plants, auto salvage yards, and landfills – across Maryland. Whenever it rains or snows, harmful chemicals, heavy metals and toxic compounds used in industrial processes at these facilities end up off-site in local waterways through stormwater. WSA’s industrial stormwater permit seeks to limit the amount of pollution from these industrial facilities through the requirement of pollution controls and monitoring, but many industrial facilities are failing to meet all necessary permit requirements.

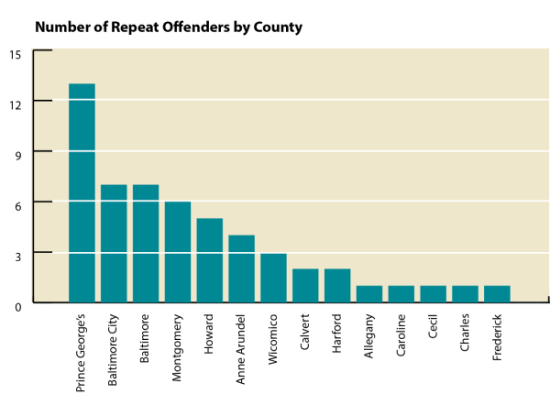

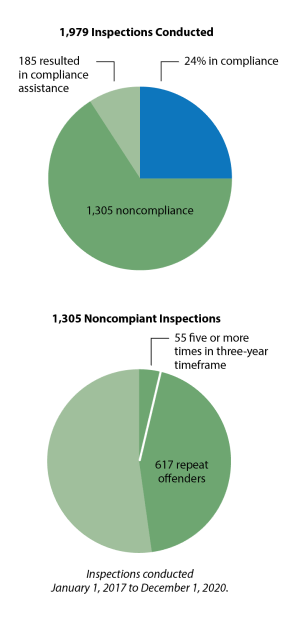

In the period from January 1, 2017 to December 1, 2020, WSA conducted 1,979 inspections, and only 475 (24 percent) of those inspections found the industrial facility to be in compliance. The inspection reports for 1,305, about two-thirds, of the total inspections directly stated “noncompliance” as the condition of the permitted site. An additional 185 inspections resulted in compliance assistance rendered, or required corrective actions or additional investigation.[4] Inspection data show that numerous facilities were in noncompliance repeatedly, and many times consecutively. Of the 1,305 inspections that resulted in direct findings of noncompliance, nearly half (617 inspections) were of facilities that were repeat offenders—meaning the facilities had previously been inspected in the same timeframe and found to be in noncompliance. In fact, from the inspections, 55 facilities were found to be in noncompliance five or more times in the three-year timeframe. The three counties with the largest concentration of repeat offenders, facilities with five or more findings of noncompliance over the three-year period, were Prince George’s County, Baltimore City, and Baltimore County. The distribution of worst offenders by county shows the environmental injustice that results from noncompliance with, and lack of enforcement of, these permits, as the worst repeat offenders are concentrated in the two counties with the highest percentage of Black residents in the state.

Further analysis demonstrates that, of 300 industrial stormwater facilities in Baltimore City and Baltimore County, 41 percent were located in census tracts in the top 25 percent of the state with respect to environmental justice burden. Additionally, the census tracts where industrial stormwater permittees are located are more overburdened by cumulative pollution impacts than the state overall. Despite the high levels of noncompliance, and the negative impacts to environmental justice and overburdened communities, formal enforcement actions against industrial stormwater permittees are relatively rare. In response to the noncompliance outlined above, there were only 14 formal enforcement actions against industrial facilities in the same three-year timeframe. |

COVID-19 Impacts to Environmental Enforcement in Maryland

In March 2020, in response to the COVID-19 outbreak, the EPA issued a dangerous (and now-rescinded) policy relaxing enforcement of environmental protections. The policy gave federally regulated facilities a free pass to not monitor or report pollution levels as required during the pandemic. It was akin to a police department announcing that they no longer would be issuing speeding tickets for traffic violations. Without monitoring, there is no way a facility can gauge whether it is polluting above its permit limits. And without fines, lawsuits, or penalties, companies have little incentive to abide by environmental laws.

While EPA’s policy was problematic for many reasons, it proved to be even more so when increased air pollution was linked to an increased risk of contracting COVID-19.

MDE responded to EPA’s policy stating it would only grant waivers of environmental requirements on a “careful and limited case-by-case basis.” However, when EPA’s enforcement discretion policy expired in August 2020, MDE still had not:

- Published any pandemic-related waivers of environmental requirements;

- Stated a clear decision-making policy for waiver determinations or permittee obligations on its website;

- Notified all permit holders of legal requirements to provide immediate notice to the state of noncompliance related to the COVID-19;

- Suspended or taken an official position on non-emergency proceedings; or

- Extended comment periods during the declared emergency.

Finally, in September 2020, MDE updated its website to include a list of all the waiver requests it had received from regulated sites. It also added new language clarifying permittees’ obligations during the pandemic and listing a point of contact for compliance and enforcement inquiries.

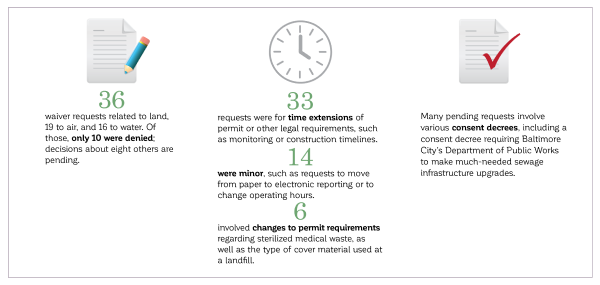

In total, MDE received 71 requests from facilities to waive environmental laws, regulations, or permits for purposes allegedly related to the pandemic. Here is the breakdown:

- Thirty-six waiver requests related to land, 19 to air, and 16 to water. Of those, only 10 were denied; decisions about eight others are pending.

- Of the remaining 53 requests, 33 (62 percent) were for time extensions of permit or other legal requirements, such as monitoring or construction timelines.

- 14 (26 percent) were minor, such as requests to move from paper to electronic reporting or to change operating hours.

- The remaining six (11 percent) involved changes to permit requirements regarding sterilized medical waste, as well as the type of cover material used at a landfill.

- Many pending requests involve various consent decrees, including a consent decree requiring Baltimore City's Department of Public Works to make much-needed sewage infrastructure upgrades.

A majority of the requests sent to MDE were related to the pandemic. But others, such as those seeking to delay important deadlines for construction projects, were not. Some of the entities requesting waivers had a track record of non-compliance before the pandemic. This suggests that some polluters may have used COVID-19 as an excuse to subvert or delay deadlines. These deadlines often work to prevent further air or water pollution. It also would not be unheard of if many entities failed to self-report violations to MDE at all.

In theory, denial of a waiver request would mean that MDE has chosen to enforce the law by taking enforcement action against any company that violated its environmental obligations. Yet here, MDE chose to deny ten waiver requests without taking any further enforcement action or issuing any fines or penalties against those facilities even if an environmental violation may have occurred. While this approach defeats the purpose of the waiver request process, it is also not out of line with the state’s downward trend in environmental enforcement activity over the last two decades, as this Scorecard demonstrates.

Nonprofits Discovering Ongoing Pollution Violations

The lack of Water & Science Administration enforcement and inspection activity creates a void that nonprofits have incredibly been forced to step into to hold violators accountable. In the past year, several high-profile examples have emerged where local environmental groups work with CAP members to spur MDE’s Water & Science Administration to take action against water polluters, either through litigation or other means.

Ecology Services waste management and recycling facility in Pasadena, Maryland

The Magothy River Association and members within CAP’s team raised concerns with the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) about a 4.38-acre waste management and recycling facility in Pasadena, Maryland. This facility, owned by Ecology Services, was suspected to be operating without a pollution discharge permit, as required by the Clean Water Act. Beginning in January 2020, MDE inspected this facility eight times and found violations during every single visit before it finally filed a lawsuit against the facility in April 2021. In addition to the company operating illegally without permit coverage, MDE noted illegal sediment tracking, improperly stored vehicle parts, stains on the ground, and other unknown liquids and containers that were exposed to rainfall. While the filing of the lawsuit is independently a great win on the enforcement front, the state tolerated an endless number of stormwater violations prior to this and if it weren’t to watchdog groups, MDE may have never pursued further action against the facility.

The facility had been operating without its required coverage under the state's industrial stormwater permit for quite some time, despite discharging sediment and other unknown pollutants into the Magothy River. This runoff prevented yellow perch from spawning in nearby parts of the Magothy this year. The Magothy River is currently impaired by sediment, bacteria, ions, metals, nutrients, and PCBs.

Patapsco and Back River wastewater treatment plants in Baltimore

CAP’s team regularly researches and assesses enforcement data related to potential polluters in areas across Maryland. The Patapsco and Back River wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) are the two largest facilities of their kind in the state, and CAP’s team has been tracking their compliance for some time. In the spring of 2021, the Baltimore Harbor Waterkeeper, who regularly conducts water quality monitoring in the local waterways around Baltimore City on behalf of Blue Water Baltimore, detected high levels of bacteria in the water near the Patapsco WWTP discharges point. At the same time, CAP member Chesapeake Legal Alliance noticed online reports of unusually high nitrogen levels at both WWTPs.

Chesapeake Legal Alliance coordinated with Blue Water Baltimore to alert MDE and ensure they were aware of the potential pollution violations. MDE sent inspectors and determined significant staffing and operational failures were causing the plants to release far more pollutants into the Back River and Patapsco River than permitted. The amount of nitrogen pollution from these two plants is so significant it could single-handedly jeopardize Maryland’s ability to reach its Bay TMDL goals. In response, Chesapeake Legal Alliance filed suit on behalf of Blue Water Baltimore in federal court against Baltimore City for violations of the Clean Water Act at both WWTPs. Maryland later filed legal action against Baltimore City for the failures at the plants.

Valley Proteins rendering plant in Linkwood

For years multiple environmental organizations have called on MDE to update the discharge permit for the Valley Proteins chicken rendering plant on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. The plant is the largest single source of nitrogen pollution in the Transquaking River and the plant has been operating on an outdated permit since 2006. This particular plant is in Linkwood, Maryland and uses chemical processes to render leftover chicken parts and bones for protein in animal feed.

Since its inception, CAP’s team has researched and assessed enforcement data related to this problematic facility. In April 2021, as a part of CAP’s work, Chesapeake Legal Alliance, representing ShoreRivers and Dorchester Citizens for Planned Growth, and Chesapeake Bay Foundation filed a notice of a potential lawsuit against Valley Proteins for its pollution violations. In just one quarter (July 2020 through September 2020), the rendering plant exceeded its ammonia pollution limits by 2,518 percent, according to EPA’s Enforcement & Compliance History Online.

In December 2021, ShoreRivers discovered what it believed to be pollution violations at the plant using a drone and reported it to MDE. Subsequent MDE inspections found significant violations at the plant and ordered it to be briefly shut down. The plant had been discharging sludge and inadequately treated wastewater into the river.

MDE filed a lawsuit against Valley Proteins in state court on February 2, shortly after the Chesapeake Legal Alliance, ShoreRivers, Dorchester Citizens for Planned Growth, and Chesapeake Bay Foundation filed their own lawsuit in federal court against Valley Proteins for violating their permit, with over 40 effluent violations over roughly two years, and exceeding pollution limits. In February, the above-named NGOs also filed a motion to intervene in MDE’s lawsuit. Without necessary changes at this rendering plant, the Transquaking River, the Chesapeake Bay, and the residents and ecosystems that rely upon them will continue to suffer.

[1] CWA Section 101(a)

[2] COMAR 26.08.04.06.

[3] Md. Dep. Env’t, Annual Enforcement & Compliance Report, Fiscal Year 2020, 19, https://mde.maryland.gov/Documents/AECR_FY20.pdf.

[4] Because the available data did not indicate the type of noncompliance, we cannot assess the severity of the noncompliance, even where “noncompliance” was the specific condition of the site.

The compliance rate for the industrial stormwater general permit is one of the lowest of the regulated sectors tracked by the Water & Science Administration.

The compliance rate for the industrial stormwater general permit is one of the lowest of the regulated sectors tracked by the Water & Science Administration.